Catholic Times contributor Chris McDonnell writes on the legacy of Tantur Rector Donald Nicholl.

I write of a place and a person. The place is on the edge of southern Jerusalem, the Tantur Ecumenical Institute, the person is Donald Nicholl.

The vision for such a place came about in the 60s following the Vatican Council where both Anglican and Protestant observers were welcomed in their attendance. Paul VI, successor of the visionary John XXIII, who first called the Council, dreamed of an ecumenical institute to continue their discussions. The following year, in 1964, the Patriarch Athenagoras met with Paul VI on the Mount of Olives and so began an opening between the Western Church and that of the East. Their meeting was to culminate when the two leaders would lift the bans of excommunication that had been in effect since the Great Schism of 1054, an extraordinary event. Jerusalem became the obvious place for an institute to further this new relationship.

The property at Tantur was purchased by the Vatican and leased to the University of Notre Dame in 1967. Due to the conflicts of the time, it was not opened until 1972. It welcomed through its doors scholars from Protestant, Roman Catholic and Orthodox backgrounds. It became an oasis of learning, prayer and hospitality in a turbulent part of the world, as it broadened its outlook to include both Jews and Muslims.

My interest in Tantur arose from reading a Journal written by one of its Rectors, a Yorkshireman, Donald Nicholl- The Testing of Hearts. A memorable book indeed that can be dipped into and the flavour of his work experienced again and again. As an academic historian, he wrote many books and articles; I have only read two of them, outside of that scholarship, his Journal of his time at Tantur and an earlier book, Holiness, without doubt prophetic works of Christian Witness.

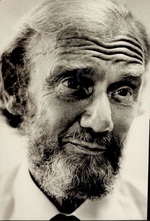

A tall man, well over six foot in height, he was by training an historian, who worked in a number of academic departments both in the UK and the US. During the Second World War, he spent time with the army in India and Asia and finally in Hong Kong.

His conversion to Catholicism came from those years and he was finally received into the Church in 1946. His academic home in England came to be Keele University in Staffordshire, taking its name from the nearby village of Keele in North Staffordshire, some twenty miles from my home. It was not his first academic home, having taught at Edinburgh during the late 40s and early 50s and at the University of California Santa Cruz in the mid 70s. It was in the early Eighties that Nicholl accepted Secondment from Keele to become Rector of the Tantur Institute and there he remained for four, at times turbulent, years, from 1981 through to 1985. Published in 1989, his journal, The Testament of Hearts, is his story of that experience. Nicholl was a layman whose Christian witness inspired many in his lifetime and whose influence still continues through his writings. His voice and encouragement as a layman should be welcome in our present efforts to repair the damage that has been the evident consequence of clericalism in our Church.

His background was simple, born into a working class family in Yorkshire, hard-working Anglicans whose practice of their faith was the framework of his early years. The depth of conviction that formed him was evident in his account of his last visit with his father, recorded in the early pages of The Testing of Hearts. Arriving at his father's bedside in early February 1979 after flying in from California, he met with the young Anglican vicar who told the family that he would come again the next day to celebrate Communion. Donald records the scene in these words. "For a moment, as he was promising to come, the vicar hesitated when he turned towards me, knowing that I am a Roman Catholic and that it was not customary for Roman Catholics to receive the Eucharist from an Anglican priest". Put in a few words was the nub of the perceived problem.

But it was no problem for a son keeping vigil with his father in his last hours. Donald goes on to say, "But he need not worry. The man lying there on his death bed-though still thirsting for breath and for life- who is my father, has taught me the meaning of Eucharist more certainly than has any theologian whose books I have read or whose sermons I have listened to."

If only these few simple words of a layman could now be widely re-visited and the depth of their meaning appreciated these forty years on. Too often we listen to those whose title and scholarship are used to justify their credibility. Donald Nicholl taught then, and still teaches now, from the experience of a simple, deep, lived-in faith. Reading his words and listening to his voice would bring comfort and a sense of reality to the Church in its present difficulties.

He was a person who was at home with diversity, seeking common ground and understanding rather than looking for the edges and tripping points of discord. The Journal is a record of careful walking amongst peoples and views that rubbed together and so often produced sparks; where he learnt the art of the balancing act and in so doing, understood the pain of division. This was highlighted in the Sunday celebration of the Eucharist and the restraints placed on individuals when it came to Receiving.

He records in his entry for 7th September 1981 "Sadly, and not for the first time in Christian history, it is precisely the act by which it is hoped to create the perfect community that seems to have precipitated most division here at Tantur". Our division over the sharing of Eucharist remains a painful reminder division within the Christian Church. Those years in Jerusalem, when bitterness between Jew and Arab spilled over into violence born out of deep mistrust, were indeed difficult times.

That Donald Nicholls steered the Tantur Institute along such a hazardous path is to his abiding credit. And today the Institute continues to flourish, its need never greater, its presence all-important in a troubled world.

He died of cancer on the evening of May 3rd ,1997, at the age of 74. The final lines in the Journal kept during his last weeks concludes with these words. "The attraction of goodness is the only way to draw others out of the world of injustice, violence, conflict and unhappiness. Not forcing others, but drawing them gracefully into communion with oneself and all creation".

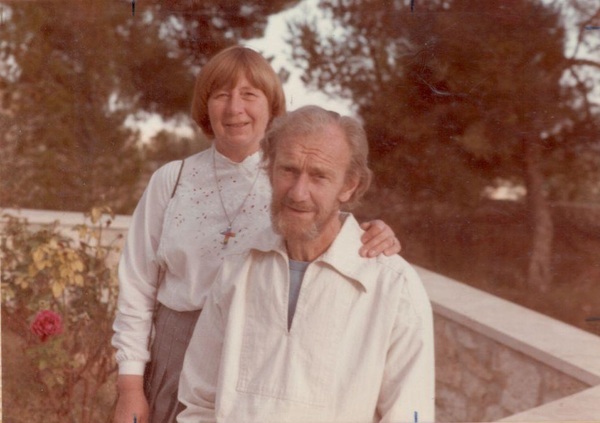

Donald Nicholl is buried in the churchyard in Keele village. After reading his words over many years I drove to that churchyard, a Saturday afternoon in the Autumn sun of late September. I went seeking his final resting place. Walking through the sea-waves of broken ground, past worn stones with their faded runes, I sought out his familiar name. Then, reaching a shaded corner of that consecrated space, I turned and saw his name, etched in fading gilt on a low black headstone, Donald Nicholl and below it that of his wife, Dorothy. All these years on, now returned to settled ground close-by his academic home, this big-framed man who walked Jerusalem streets and the hills beyond, lies still, his voice gone yet his words remain.

The words of Julian of Norwich are inscribed on that small stone -"All will be well". The silent echo of a medieval phrase tell of a pilgrim's completed journey, one who is now at peace in the earth of home.

A shorter version of this article first ran in the October 12th, 2018 edition of Catholic Times (UK). Photos of Donald and Dorothy Nicholl ctsy. Tantur. Photo of the Nicholl tombstone ctsy. Chris McDonnell.